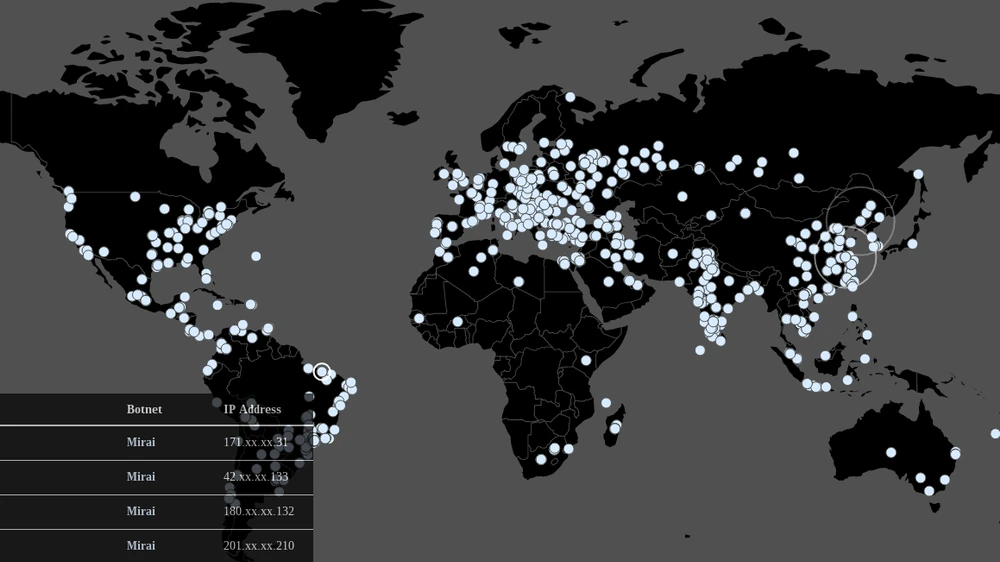

It’s not exactly a secret that quite a few devices within the Internet of Things are insecure. Probably the best known example of this was the Mirai Botnet, which literally broke the internet by using connected consumer devices. One of the things that was missing to prevent these sort of attacks is a security standard for IoT devices.

The European Telecommunications Standards Institute, better known by their abbreviation ETSI, has created a cybersecurity standard which is aimed at those connected devices. Cyber Protection Magazin spoke with the Chair of their Technical Committee on Cybersecurity, Alex Leadbeater, about the new standard.

Cyber Protection Magazine: Alex, with your latest test specification TS 103 701 and the underlying standard EN 303 645, your objective was to create something which is comparable to the CE standards, which we have in Europe for the safety of consumer products. This new standard, is that something like a CE label for security for technical IoT and smart home devices?

Alex Leadbeater: It can be. But I think it’s worth setting in context. ETSI produces standards, but is not a certification authority. We produce advice, guidance, recommendation, European norms, all sorts of good stuff. However, whereas the CE markings are a full accredited scheme, EN 303 645 is for third party organizations, like national bodies, the European test labs or other trade associations to set that certification up. But if we look at the bigger picture then it is likely that EN 603 645 will end up being something very close to the CE marking.

Cyber Protection Magazine: And what does the new the standard actually entail? In a nutshell, what are the main requirements for someone who wants to follow the directive?

“A significant number of attacks on IoT could have been stopped.”

Alex Leadbeater: Again a little bit of a context on the EN. A number of European governments and others have identified some interesting weaknesses in a lot of IoT security products, both in Europe and globally. That has driven, shall we say, a certain amount of excitement, while the photos of certain brands of cars upside down in ditches and certain child’s dolls with really crap security have drawn headlines. The EN is a product of some work in the UK and indeed also with BSI in Germany to try and raise the bar on cybersecurity across the board. And it focuses on 13 key simple areas. Those 13 map into around about 100 provisions, some of which are mandatory, some of which are strongly recommended. And from a GDPR perspective, nearly all of them you would expect to have to do, except if your product doesn’t have certain features. Let’s look at the top three examples:

- no universal default passwords,

- implementing a means to report vulnerabilities

- keep software up to date.

Now, if we take those three and then look at things like the Mirai botnets and a significant number of the other ransomware attacks or malware attacks on IoT devices over the last 5 to 10 years. Had every single product on the marketplace complied with those basic three, then none of those attacks would have happened. Now, that’s not to say other attacks wouldn’t have happened, because the cybercriminals would have just tried a bit harder. But the basic low level attacks that we’ve seen indiscriminately on IoT would have been entirely stopped by those three alone. The remaining ten then cover topics like data security, software integrity for updates and the life cycle of personal data.

Now, if you actually were to go and speak to a manufacturer and say, well, here’s one of the 13 provisions, does your product comply with that? Or if you’ve had a data protection breach and one of the member states asks, why have you not complied with this? Why have you not solved this problem? You’d struggle to justify why you haven’t met those criteria.

None of those requirements are particularly onerous. None of them are particularly earth shattering. And indeed, if you were to look across the ICT sector, for example, Microsoft based products or Android based products, most of those products long since covered all these sorts of vulnerabilities years ago. These were the sorts of vulnerabilities we were talking about when Windows 95 appeared on the scene. They are nothing new. However, a lot of IoT security very much rolls the clock back on cybersecurity protection. So, the EN standard is setting up a baseline. It’s not intended to protect devices in nuclear power stations. That said, if we get to a point where all of the products in the market meet all 13 provisions and all of the requirements that distill from that, then we will likely look to raise the bar further.

IoT Security rolls the clock back on cyber protection

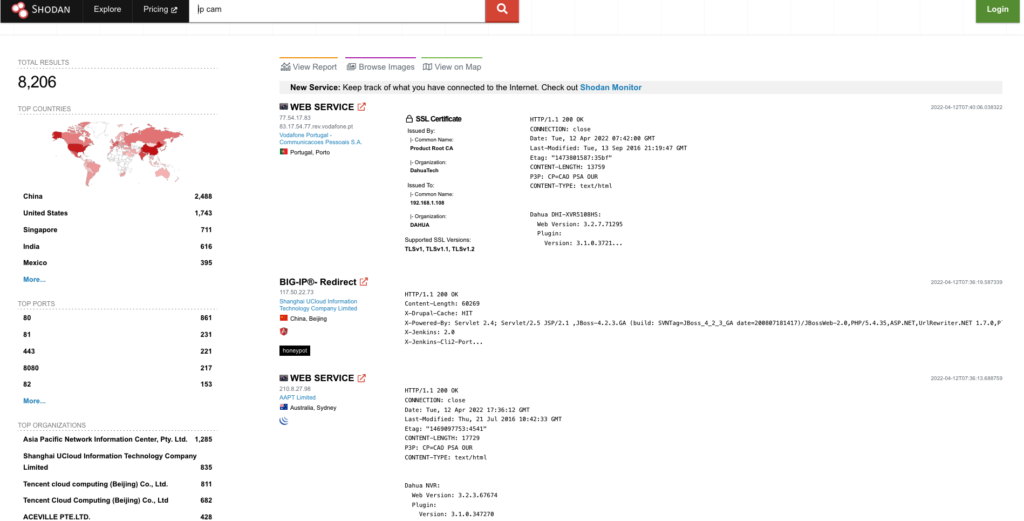

So it’s very much about setting a bar that is achievable and sort of attainable for manufacturers. If you look at the market today, there are clearly some products that will get close to all 13 and indeed there are some products that have been certified to meet the EN via certain certification schemes. There are good products on the market and there are responsible manufacturers. However, a good 50 or 60% of the devices don’t get anywhere near at least half of those, let alone all of them. To take the example of default passwords: quite a few device still come out of the box with the default admin password in 2022. That’s really not good enough.

Cyber Protection Magazine: Actually, that surprises me. Well, it doesn’t really surprise me that default password is the one requirement that most do not meet. But I would have thought that the having a channel for a vulnerability would be a more common failure, especially if you look at no name manufacturers from China. Or is it more like that they claim they have a channel, but in reality no one ever picks up the phone?

Alex Leadbeater: We’ll come to the CVD (Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure) in a second because it’s probably the largest gap, but it’s not the largest impact. Having default passwords is by far the largest impact because the amount of effort required to exploit it is minimal and the number of devices that have those default passwords is massive. Hence, on scale it is by far and away the most risky of the set. However, in terms of the number of devices by manufacturer rather than sheer scale of numbers, then the missing CVD ends up as being a different sort of highest risk.

“The industry as a whole is really not trying”

When we first started working on the EN, research told us that around 8% of manufacturers in the IoT market back in 2018, 2019 had a CVD scheme. As of late 2021, that number sits at about 20%. Now if you think about that in numeric terms, actually a 300% increase or thereabouts is actually really, really good. However, when you look at it in absolute number terms, only 20% of the market having a CVD scheme is really, really rubbish. There is no other way of stating that or glossing over it. 20% shows that the industry as a whole is really not trying. Now, clearly, a number of the Chinese manufacturers are going to fall into that 80%, but in reality, a lot of European manufacturers don’t have a CVD either. The big ones, like Siemens or Bosch for example, will have CVD capabilities. However, a lot of reasonably sized European companies don’t, and most of the SMEs won’t either. We have quite a large hill to climb in this. At the rate of improvement, we would probably be looking at another 10 to 20 years before we got to 80% or 90%, let alone 100%.

Lots of companies don’t have the scale or the manpower or the expertise to deal with that sort of aspect. Therefore, the ETSI document is very much an introduction to them in terms of what their processes need to be.

To name a few examples, take having a point of contact. Having a form on the front page of your website is great, but you need to have the means to actually then take that vulnerability in, consume it within your organization and have the processes in place to get the products updated, especially if you’ve got a multi vendor supply chain. If you’re not producing the product yourself, you’re buying in subcomponents or software, then that process needs to extend to your supply chain and then you need various other processes to get the products updated. The organizations need that process, and they also need to have a responsibility to accept that their products may not be perfect. They need to stand up and say: “if there is a vulnerability, we’ll try and fix it”. All of that requires a cultural ethos in those organizations.

if there is a vulnerability, we’ll try and fix it

Cyber Protection Magazine: You mentioned earlier that companies who need IoT devices in their operations will probably ask a supplier, a vendor, why are you not more compliant or following the standard? And those suppliers will probably have to comply at some point at the time, because the buyers are also aware of the cybersecurity issues and they don’t want to buy something insecure. But what about the consumer part? Because if a consumer has the choice between a device which might not be so secure, but it’s €5 cheaper, they’ll go for the €5 cheaper device, and don’t really care about the security.

Alex Leadbeater: You seem to have, shall we say, rather more faith in the purchasing departments of large enterprises than perhaps I do from my experience in the security department. I’m rather more skeptical. But if they were asking those due diligence questions, I think they’d be far less security issues on the European market than there are.

But extending that out to the consumer, and I think the same applies to the buyers in the enterprises, it’s a lack of awareness as to what they should be looking for. The EN is the first real baseline standard intended as a European baseline for this. Obviously some organizations are well aware of its existence. We had a lot of great companies involved in the creation of it and the word is getting out, and there are a number of consumer organizations are very much taking it to heart.

“The EN is the first real baseline standard”

Nevertheless, on the whole there is a lack of awareness in the space and that extends into the consumers. Clearly for consumers today, money is tight, so they are clearly pressured to buy the cheapest device they can get. That said, if you look at the number of consumers in the market who aspire and indeed buy iPhones shows that people will pay for quality products. Therefore the challenge is not necessarily the price. The challenge is causing people to think about the cybersecurity of the product they’re buying. That is probably the bigger barrier to adoption rather than the absolute cost.

No plans for cybersecurity traffic lights

The other thing that would obviously help would be to have the equivalent of a traffic light sticker or something on the back, but there isn’t a plan in Europe currently. As much as I’d love to see the ETSI logo on the back of every product, trying to get the consumer to understand and look at the back of the box and do so in a way that they can easily understand “This is a good cyber security product”, that’s a really difficult nut to crack. And at the moment, there doesn’t seem to be much of a political drive to do that.

Cyber Protection Magazine: Now, wouldn’t it be a possibility, to take the Smart home market, for example the new “Matter” standard organization and tell them: “How about you only certify those devices which also can prove that they are secure according to the standard”?

Alex Leadbeater: Yes, absolutely. For example DCMS in the UK and BSI in Germany are driving a lot of that engagement and I believe they have had some conversations with the Matter organization. And there is a push to try and align certification schemes, but it requires a certain political will to try and encourage those.

Cyber Protection Magazine: Let’s move from smart home over to IoT, especially with the war in Ukraine going on. What would you say is the situation today in the industrial environment and what might it be going to be in the future? What is the state of security, is adoption accelerating because of the war?

“clearly there is a rising threat”

Alex Leadbeater: Obviously, there have been a number of coincidental timing failures of systems in Europe. I mean, the British Airways website going down just happened miraculously hours after an airspace ban was given to the Russians and Aeroflot. Clearly, it was obviously just a fluke failure of the right system, as they publicly stated. But you can clearly draw on your own conclusions as a cybersecurity professional, that coincidental timing looks remarkably like somebody’s given that a bit of encouragement. So clearly there is a rising threat. What’s interesting is the difference between the enterprise or the industrial and the consumer landscape. Clearly defending a nuclear power station from cyber attack is more critical than defending an individual smart thermostat.

What’s also interesting, however, is that most consumer devices are obviously designed to be on the Internet, whereas industrial devices generally aren’t. Consumer devices have personal data on them, industrial devices generally don’t. Industrial devices are very often more sensor based rather than require full interaction.

IIoT: Higher requirements, but identical baseline

So in a lot of ways, the industrial devices may well be simpler to secure in some circumstances. Clearly, if that’s a connected car, then that’s a seriously complicated, and securing that is more complicated. And it introduces a safety critical risk that a standard smartwatch or a thermostat in the home doesn’t have.

But while industrial IoT has different and substantially higher requirements, actually the EN, though written for consumers, is equally applicable. Take the example of best practice cryptography. The definition of best practice cryptography for an industrial process that is needing to withstand nation state actor attack versus a child’s doll in a home is not much different. An industrial device is higher grade than the consumer device, but the actual requirement for best practice cryptography is identical. The requirement for keeping your software up to date is identical. Now, that may be more difficult to do in an industrial process because, for example, you can’t necessarily take the devices offline. But you could apply the EN to industrial processes as well. The only difference is that your benchmark in terms of what is best practice cryptography, again as an example, differs, but they’re not massively different.

“The EN can have a role to play”

The other thing with consumer devices, as I said, is that most of them were always intended to be network connected. Interesting for the industry devices is that a lot of the processes that seem to be coming under fire are things that have effectively been retrospectively connected. In other words, they were legacy equipment that wasn’t Internet connected that all of a sudden somebody wants to make smart. There’s a different set of risks and threats in play there. It’s quite a complex landscape.

In a lot of industrial sectors, though, there are already cybersecurity standards in place. For example, the automotive industry, after that particular incident with the car ending up in a ditch after the Bluetooth interface was hacked, did improve its ideas. So there are some sector specific standards relating to safety and medical and similar, that have introduced certain cybersecurity requirements. Hence, there are little sort of islands of security but what there isn’t, is a more generic form. The EN can have a role to play in that.

This interview has been taken from our second special magazine issue. You can find – and download – our special issues here.