Election security has been a significant news story for half a decade, much of it focused on the technology of voting. The focus should be on people, however, specifically the critics of election security.

Harry Hursti, perhaps the best-known expert on voting machines, has been examining security flaws in voting machines and while he finds them seriously obsolete he doesn’t see them as a significant problem in securing voting information.

Hursti buys used and obsoleted voting machines for use in an annual hack-a-thon he holds at the Black Hat Conference in Las Vegas. He recently made the news when the state of Michigan decided to sue him for the return of one of the state machines he bought on eBay. It wasn’t a new occurrence. Hursti and his team have been buying the machines since 2007, often under state contracts to ensure security. This seemed to be a surprise to the State of Michigan.

Pushing paper

Hursti’s work has been instrumental in limiting but not eliminating the use of digital voting machines. “Because of the work security practitioners have done in elections, most US elections are done with paper ballots,” he explained, So if there’s something happening wrong going wrong in the voting machines, you can always order it and you can recover by recounting the paper ballots.”

Paper ballots are easier to track, validate and audit. They also facilitate vote-by-mail systems. Electronic machines started coming into vogue in the 1970s but machine failure was common and researchers like Hurtsi pointed to how easy the machine was to hack driving counties back to paper ballots.

According to a study by Reuters, 70 percent of all US voters use landmarked ballots and another 23 percent use machines that mark paper ballots. Only 7 percent of counties are still using direct recording electronic (DRE) machines and that number is dropping rapidly. The Brennan Center, which has been studying the use of DREs since 2014 said that the number of states using the digital machines dropped from 43 to 16 in 2012 and then to 7 in 2021. By November 2022, less than 6 percent of voters will be using DREs without the ability to produce paper ballots. Louisiana is the only state exclusively using DREs for this election.

So what’s the problem?

The rise of misinformation and partisan interference in election processes has created dozens of security breaches, some which may not be obvious. In the past two years:

- Colorado — GOP operatives, under the direction of a county clerk entered a Mesa County warehouse where election equipment was secured, copied hard drives and election-management software, and then fled.

- Arizona — Election officials had to replace voting machines in Maricopa County after GOP political operatives and other unaccredited people gained extensive access to the machines for a widely criticized review of the 2020 results.

- Pennsylvania — The secretary of state decertified voting equipment in rural Fulton County after officials there allowed a private company to participate in a similar review.

When unaccredited, unsupervised people access the machines and data. it is impossible for election officials to guarantee that the machines have not been tampered with. According to Hursti, a DRE can be reprogrammed with a $20 FPGA processor that would “pass every check and get always be able to change the outcome of the election without changing the software. That makes the CPU, itself, malicious.” The only solution to that problem is to frequently reprogram or replace them.

Certification is key

The biggest problem in securing elections is not hacked software, equipment glitches, or outdated systems. The biggest problem, as explained above, is allowing uncertified “experts” physical access to the equipment and the data, either in physical or electronic forms. Blocking that access is more difficult than one might think.

Every state, and every county and parish within those states, has different rules and standards for election workers and some of those standards are blatantly partisan and inadequate.

For example, California selects most election workers without requiring them to be registered to any particular party. Election officials overseeing their work are chosen equally from both major parties. California also requires a minimum of two hours of training about how to do the work and secure the ballots. Alabama, on the other hand, chooses workers based on whatever party happens to control the state legislature as of the previous election and requires no training whatsoever.

In one aspect, the US election system complexity makes it almost impossible to influence the entire system. In other aspects, the inconsistencies make the system vulnerable to claims of fraud and mismanagement when neither exists and overlooks standardized bad practices.

Legislation stalled

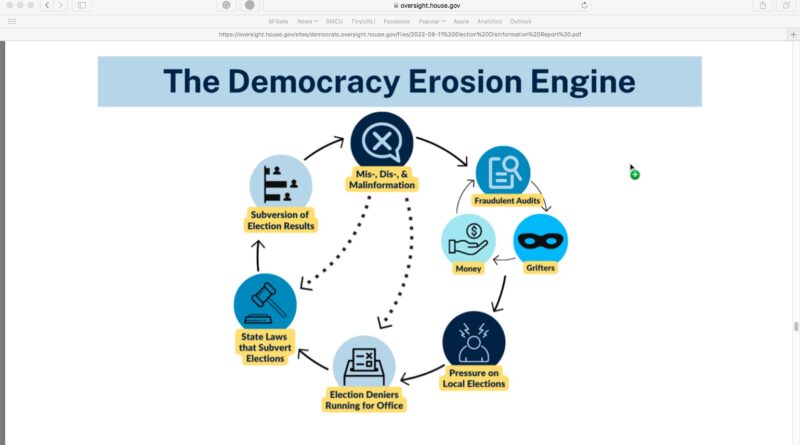

The U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Reform identified a network of malicious actors encouraging local elected officials to approve “fraudulent audits.” Those actors generated misinformation, intimidated election officials that refused, and pushed legislation that validated attempts to overturn valid election results. The committee determined that this domestic activity is the single, largest weakness of the American elections process. Even foreign misinformation and meddling come close to the level of influence.

In their report Issued in August, the committee said, “Misinformation about election integrity increases the likelihood that bad-faith actors will successfully subvert legitimate election results. The spread of lies and distorted information about how votes are cast and counted, who is voting, and who is doing the counting, creates opportunities for bad faith actors to prevent the legitimate winner of an election from taking office.”

Good luck with that

Doing something about the problem on a federal level is not going to be easy. Several laws are in the US House of representatives to protect election workers and officials However, none of the bills has bipartisan support. Two of the bills, HR 4722 and HR 4064, criminalize intimidation of the workers and ban carrying firearms within 100 feet of a polling station. The bills, introduced more than a year ago, languish in committee with a 4 percent chance of passage.

In the end, voters need to decide whether they believe strangers in social media about the state of our election system and where the real dangers are, or the people that are going the actual work in making sure the system, however flawed, is not as bad as they think.

Lou Covey is the Chief Editor for Cyber Protection Magazine. In 50 years as a journalist he covered American politics, education, religious history, women’s fashion, music, marketing technology, renewable energy, semiconductors, avionics. He is currently focused on cybersecurity and artificial intelligence. He published a book on renewable energy policy in 2020 and is writing a second one on technology aptitude. He hosts the Crucial Tech podcast.